If you’ve ever taken a literature class at Wheaton, chances are you’ve been asked to interpret a novel or a poem through a religious lens. Or maybe you’re in a BITH class and your professor has assigned you a non-theological text to analyze in light of your theological studies, perhaps a work of fiction. If you’ve never written something in the genre of Religion and Literature Studies, it can be confusing to understand what to write about, especially because this discipline has some similarities and differences with other genres.

In this post, I’ll break down what writing in Religion and Literature Studies looks like. What does a literary analysis look like when it considers a religious focus? And how does this genre differ from others?

The basics: What is Religion and Literature Studies?

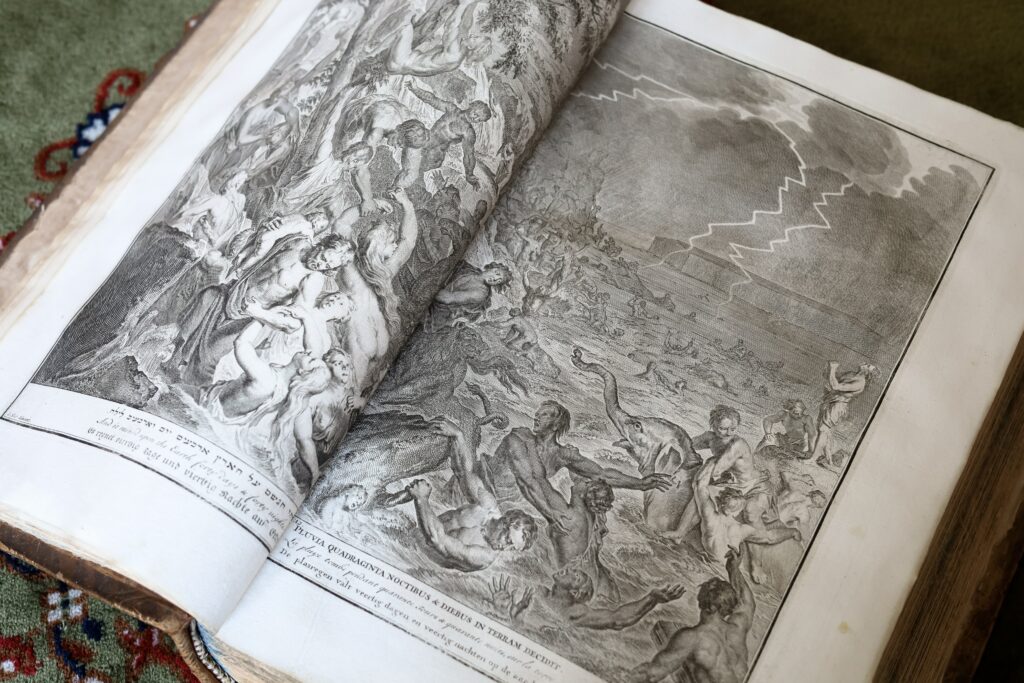

Religion and Literature Studies is an interdisciplinary field that draws on theological inquiry to explore questions about literary texts. For example, a scholar might discuss Eucharistic imagery in Goblin Market by Christina Rossetti, or she might consider parallels between the flood narratives in Genesis and One Hundred Years of Solitude by Gabriel García Márquez.

In the words of the Notre Dame-based journal Religion & Literature, both religion and literature are “crucial human concerns,” and a quick scroll through their JSTOR page reveals that there are endless ways to combine these topics. Both are so fascinating that we can’t help but combine them.

How do we write about religion and literature?

If you’ve been in English or other language and literature classes before, good news! Everything you learned about how to conduct a literary analysis applies. You’re pulling evidence from the text and using close reading to prove your points. You’re still working on analysis and interpretation—answering the “how” and “why” of the text. Only in this case, your interpretation will have to do with some element of theology or religious history.

In order to generate a research question in this field, one approach is to pick a doctrine: for example, the Trinity, salvation, or the image of God. Then you can look for how the text responds to that idea and what that response might reveal about the doctrine and the text itself. I took this approach writing an essay on George Eliot’s Middlemarch. I read it through the lens of vocation to see how Eliot grappled with this concept at the cusp of the Industrial Revolution:

I contend that Mary Garth, who is both a woman and a worker, emerges as an exemplar of vocation in Middlemarch precisely because she makes peace with—and makes the most of—her limitations . . . In including this character as an example, Eliot redefines vocation in her post-Christian moral framework as a set of callings from a social context, providing a corrective to the idolization of work.

Other questions you can ask yourself to get an idea of what to write about:

- What allusions to the Bible/another religious text do I see in this literary piece? Why are those significant?

- How does this text depict religious experience among different races, classes, and genders?

- What kind of political power did various religions and sects have at the time this work was written? And how are those groups depicted in the text?

- How does this text fit into the historical development of a certain doctrine (e.g. predestination)?

What Religion and Literature Studies is not

When you write at the intersection of religion and literature, it can be tempting to veer into another genre. In order to avoid straying out of Religion and Literature Studies, let’s consider what the field is not meant to do.

Writing about religion and literature is not the same as writing…

- A heresy-spotting invective. Sometimes, it can feel rewarding to criticize an author’s message if it differs from your understanding of Christianity. For example, maybe you think Emily Dickinson’s idea of God is anti-Trinitarian. It can be tempting to point out this disparity as a “gotcha” and leave it there, but that’s not the most effective strategy in this discipline. Not everyone in the field of religion and literature studies agrees on what they believe, so your audience likely will not be interested in whether or not a thinker is “orthodox” or not. A more interesting question for your audience would be how and why the author diverges from their religious tradition.

- A sermon. Similarly, the goal of religion and literature studies is not to convince someone of a certain theological belief. In other words, you’re not trying to get the audience to agree with your take on predestination. Instead, you’re trying to reveal the text’s take on it.

- A Bible study or devotional. Remember that this is a work of literature and not the Bible. Many people who have encountered texts in Bible study settings tend to approach all texts with a Bible-study mindset: how can I understand the author’s intent? What is the moral insight that this passage is communicating to me, and how can I apply it to my daily life? These questions are worthy ones to consider, but in an academic paper about a work of literature, it may not be the kind of question that other scholars in the field will resonate with.

- A personal reflection. While literature absolutely can and should be a tool of spiritual growth, an academic paper isn’t the best place to reflect on how a poem deepened your own spiritual life. However, reflective journaling is a great way to explore these ideas.

A note on using the Bible as a source

If the text you’re writing about comes from a Christian tradition, it’s likely that you’ll need to quote the Bible at some point. However, be careful how you use the Bible as evidence. Are you appealing to the Bible as a final authority to prove a point, or are you analyzing its effect in the context of the literary text in question? Because your audience may not share your idea of scriptural authority, the Bible will not be considered authoritative by many readers in the field.

If you’d like to learn more about using the Bible in academic writing, we have a blog post covering the subject at the link.

Conclusion

Literature and theology are both fields that engage the deepest questions of the human experience, so it’s only natural that a field exists at their intersection. If you’re not used to talking about religion as it relates to literature, don’t hesitate to give it a try. You never know what new insights you might discover about a literary text or a theological idea when you look at one through the lens of the other.