I had never heard the name “Christian Wiman” until three of my classes this semester assigned me to go to a recent lecture at Wheaton College entitled “The Art of Faith, the Faith of Art.” I was told he was one of the foremost Christian poets of our modern time and that the event would be worthwhile for any aspiring writer. A writer, philosopher, and theologian, Christian Wiman connected these subjects throughout his lecture.

He wore a simple brown vest over a blue dress shirt and a beanie on his head. He carried himself gently, humble and soft-spoken, with a steady and sure cadence. He gave his lecture with the authority of an essayist and the rhythm of a poet, never stumbling over his words or breaking tempo. I found myself entranced as he read the poems of George Herbert and Anna Kamieńska, as he brought them together in art and faith through his own work.

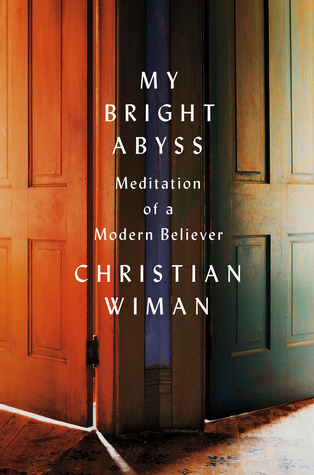

Published 10 years ago, My Bright Abyss is a collection of personal essays exploring Wiman’s struggle with a rare blood cancer. He writes as a man familiar with the face of death, but one never broken by its foreboding presence in his life. He does not write death off as something to be looked forward to, but as a certain reality to be prepared for. Hearing Wiman talk about the book now is a different experience than reading it, as he has been in remission for years, but a prophetic urgency in his book remains with potent clarity. Wiman believes that Christianity and writing have much to do with each other. And this is the main theme of his writing: Christians ought to write precisely because writing is a faithful expression of the struggle and beauty that comes from a life devoted to the pursuit of faith in God.

Looking into the Abyss

My God my bright abyss

into which all my longing will not go

once more I come to the edge of all I know

and believing nothing believe in this:

Wiman begins his book with this short poem, which he says remains unfinished. The abyss Wiman describes is the very essence of God, the infinite mystery of faith and struggle that inevitably accompanies the faithful life. The poem acts as a sort of invocation to the reader and to the author himself, ending on a colon, with the rest of the collection of essays fulfilling what Wiman calls “its ending.”

Outside of his usual genre, Wiman chose to write prose-style memoirs as opposed to poetry. While he does not tire of “poetic beauty,” Wiman desires “to speak more clearly” about his life in the face of death. What follows is a collection of essays ranging in topic, including his experiences in the Baptist church of his childhood, living in a dusty West Texas town, his journey with the loss and reclamation of faith, and his position “looking through the actual lens of death.” These essays collectively aim to explore what it means to be an artist and a Christian in the face of suffering.

Wiman, in the first chapter of this book, invites the reader to challenge their conception of faith, claiming, “there is no way to ‘return to the faith of your childhood.’” What I believe Wiman suggests here, and throughout the rest of the book, is that a stagnant faith is a brittle one, bound to shatter in front of us if our lives do not grow alongside it. As someone more intimately acquainted with suffering than many, Wiman’s point is important to emphasize. Unless one is open to their faith being transformed and challenged while reading through these essays, as Wiman’s was and is, the rest of his book will fall on deaf ears.

There seems to be an important claim made about the convergence of writing and faith here. Wiman’s essays are defined, most clearly, by the way their meaning unravels throughout the writing process. It is a call for the reader and the writer to be honest with themselves, not seeking to write easy solutions, but to sit in a place of doubt, trusting that your faith will grow and be changed through the writing of it.

Christ is Contingency

What is immediately striking about Wiman’s book is the way he writes about Christ’s actual presence, both in the life of the artist and the individual. He unabashedly and unapologetically connects Jesus and theology with more “secular” figures such as Rainer Maria Rilke, William Wordsworth, and Richard Wilbur. But it seems, to me at least, that the reason Wiman can weave these things together is that he finds reading Dietrich Bonhoeffer just as applicable as he does T.S. Eliot. While we constantly “try to bring God down to our level,” Wiman sees that our art can be lifted up by God to become a higher thing than we would naturally be capable of.

“Christ is contingency” is a presiding theme in Wiman’s work throughout the book in reference to art and suffering. It is a nuanced idea, almost a theodicy, that explores Christ’s precedence over reality. To say that Christ is contingent means that Christ has become part of our reality through the incarnation. This means that Christ understands our experiences and experiences them with us. Because he has stepped into human existence, Christ has eternally tied himself to what it means to be an embodied person, and we can look at him the same way in our writing. As writers, and especially Christian writers, our work finds its meaning in the way Christ can actively step into our work, our struggle, our writing, and truly change the way we navigate our “abysmal” experiences, which inevitably accompany life. The point here is the way Wiman sees God as one who does not simply preside distantly but who is closely entwined with us and cares about the things we think about.

[Love] is radical and true, refusing to let go of easy-to-swallow conclusions, and finds its perfection in the uneasiness of the abyss.

Throughout the presentation of the book, Wiman builds the case for a binding agent that holds faith, humanity, art, and reality together: love. This might seem like a cliché that has been beaten to death over and over again, but Wiman’s understanding of love is distinct. It is radical and true, refusing to let go of easy-to-swallow conclusions, and finds its perfection in the uneasiness of the abyss. Wiman does not leave the abyss with all of the solutions he seeks or a new wisdom that transcends his suffering. The answer does not come easily, and, in some ways, there is no satisfying resolution to the questions he has. Instead, he has these memories, an embrace of grace, and a plea for himself that leads him to “believe in this.” And this is precisely what we mean when we say writing is a faithful expression of the Christian life—it struggles through the story and narrative, refusing to let go until it reaches some kind of meaning, some kind of resolution, that blesses the writer.